Suppose you own a townhouse in New York City with Class B units or Single Room Occupancy (SRO) rooms. In that case, you hold more than just a building — you have a property woven into the city’s housing history, with a set of regulations that can shape its future value.

Many of these properties began their lives as grand single-family residences in neighborhoods such as Harlem, the Upper West Side, and Brooklyn’s brownstone belts. Over time, economic shifts and housing demand led owners to rent out rooms, sometimes informally. They sometimes act as legally established SROs, creating steady income streams to offset taxes, utilities, and repairs.

Fast-forward to today: a townhouse with more than six legal SRO units is almost certainly subject to New York City’s rent stabilization laws. These protections — designed to preserve affordable housing — also limit how much you can raise rents, when you can reclaim units, and, in many cases, how you can legally change the building’s use.

For longtime owners, this means navigating strict regulations while maintaining aging buildings. For heirs, it often means inheriting not just property, but tenants, legal restrictions, and a complex financial equation.

This guide offers:

- A concise explanation of what Class B units and SRO townhouses in NYC are under the law

- The historical forces — from the Great Depression to the 1983 SRO Law — that created today’s rules

- How do these designations influence market value and buyer interest

- Strategic options for owners and heirs, from legal conversion to sale

Important: This article is for informational purposes only. It is not legal advice. Every property is unique. Consult a qualified NYC real estate attorney before making decisions.

Receive the Private Edition

Understanding Class B Units and SRO Townhouses in NYC

To navigate your options, you first need to know how your building is legally defined. In New York City, the classification process begins with the issuance of a certificate of occupancy and the application of the New York State Multiple Dwelling Law (MDL).

A Class B multiple dwelling is defined as a building designed for transient or semi-transient occupancy — meaning it was intended for people staying days, weeks, or a few months, not permanent residents. In NYC, this category overwhelmingly includes Single Room Occupancy (SRO) housing.

An SRO unit is typically:

- A single room within a larger building

- Rented to an individual or small household

- Without its kitchen, and sometimes without a private bathroom

- Sharing facilities such as bathrooms or kitchens with other tenants

Many SRO buildings began as pre-war townhouses built for single families. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as the city’s population grew rapidly, owners subdivided these homes, sometimes through formal conversions and sometimes informally, to create affordable, centrally located housing for workers, recent immigrants, and individuals in transition.

Why this matters today:

- If your building is legally classified as Class B and contains more than six SRO units, it is likely subject to rent stabilization laws. This means:

- Strong eviction protections for tenants

- Annual rent increase limits set by the NYC Rent Guidelines Board

- Restrictions on altering use — vacancy do not automatically allow you to convert units or change the building’s classification without city approval.

Many owners only realize the full weight of these rules when they attempt to sell, refinance, or renovate, and by then, their flexibility is already reduced.

One of the smartest early steps is to review your certificate of occupancy, HPD registration, and Department of Buildings records with a professional familiar with NYC’s housing code. This will determine your building’s actual legal status and guide every other decision you make.

A Brief History of Class B Units and SRO Townhouses in NYC

Understanding why Class B units and SRO townhouses in NYC are heavily regulated today requires examining more than a century of housing shifts.

Early 1900s: The Birth of the SRO Model

In the early 20th century, New York City was swelling with new arrivals — immigrants, rural migrants, and laborers drawn by the city’s growing industries. Many of the elegant brownstones and limestone townhouses built during the Gilded Age proved too large and expensive for a single household to maintain.

Owners began subdividing these properties into smaller rooms for rent, often with shared kitchens or bathrooms. This flexible, inexpensive arrangement — close to employment opportunities and available without a long-term lease — became known as Single Room Occupancy housing. It offered a lifeline to working-class residents and provided a steady income to owners.

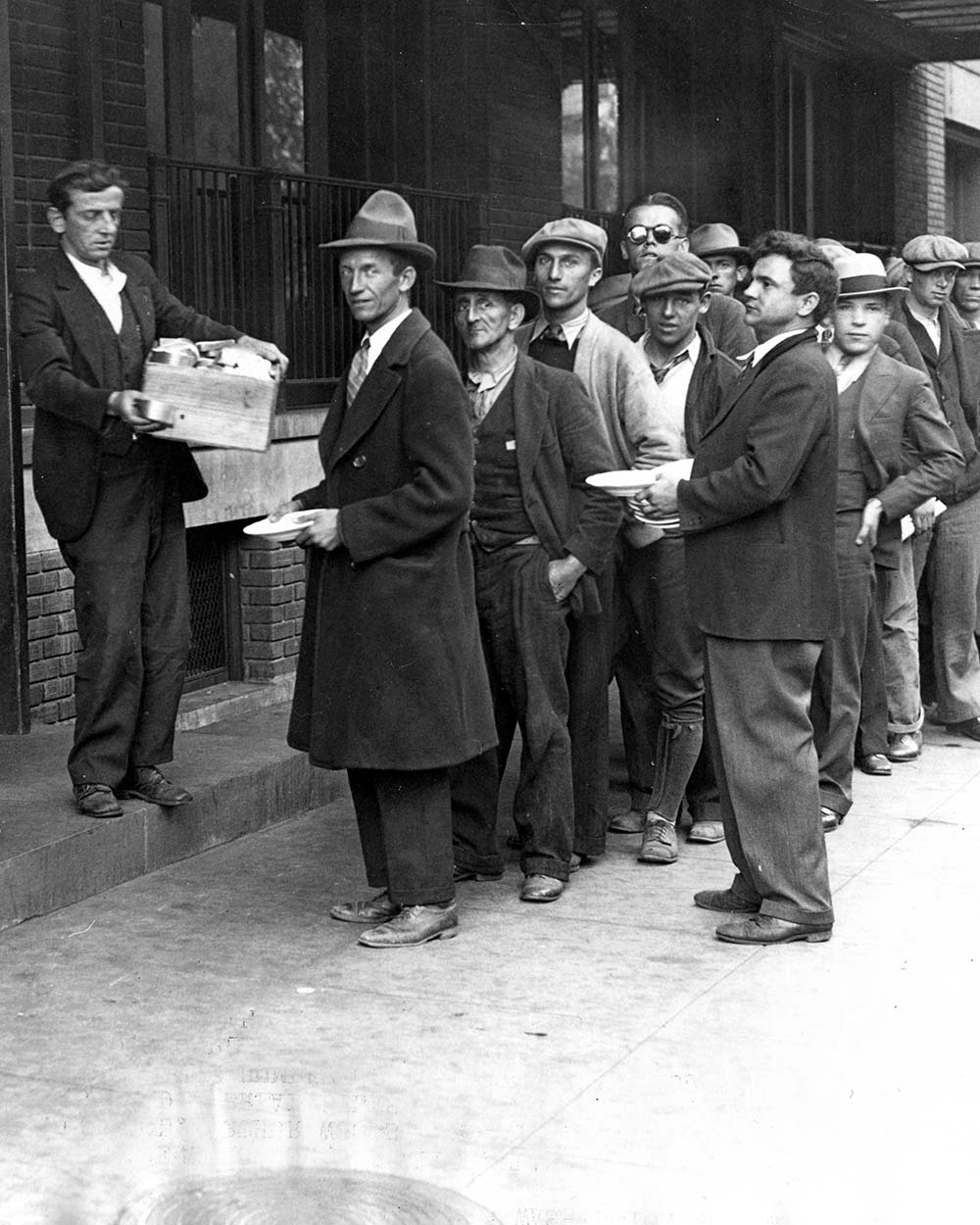

1930s: The Great Depression and the Expansion of SRO Housing

The Great Depression reshaped NYC housing. Widespread job loss and falling wages prompted many New Yorkers to move out of larger apartments. Townhouse owners, struggling with mortgages and property taxes, turned to SRO rentals even more aggressively.

Some took in a few boarders; others converted entire floors into rentable rooms. Because housing codes were looser at the time, many of these conversions occurred informally, with no permits and minimal alterations. The “boarding house” model became embedded in neighborhoods that had once been strictly single-family.

SROs in this era served two purposes: they kept struggling owners afloat and provided the cheapest form of private housing for thousands of residents who couldn’t afford a whole apartment.

Postwar Period: Stability and Stigma

By the mid-20th century, SROs were an established part of NYC’s housing landscape. They housed a mix of retirees, single workers, and people in transition. However, not all owners maintained their buildings well. Some allowed overcrowding or deferred major repairs, giving SROs a reputation for substandard living conditions.

Meanwhile, rising property values and the push for modern apartment construction led to the mass demolition and conversion of SRO housing into higher-rent units. This accelerated in the 1960s and 1970s, contributing to the affordable housing shortage that still plagues the city today.

1970s–1980s: Preservation Through Regulation

In response to the loss of affordable housing and concerns about tenant displacement, the city passed increasingly strict laws:

- 1950s–1960s: Fire and building codes tightened — better lighting, ventilation, and safety features were required.

- 1970s: Demolition and conversion of SROs were restricted to slow the loss of units.

- 1983 SRO Law: Made it illegal to convert or demolish SRO units without city approval and, in many cases, without replacing them with comparable affordable housing.

- Rent Stabilization Expansion: SRO buildings with six or more units were brought under rent stabilization, limiting rent increases and strengthening tenant protections.

These measures solidified SROs as a protected form of housing, ensuring affordability while also imposing legal and financial constraints that owners continue to grapple with today.

How Class B Units and SRO Townhouses Affect Property Value in NYC

Owning a Class B unit or SRO townhouse in NYC is fundamentally different from owning a vacant, Class A single-family property. While these buildings can still hold substantial value, the market assesses them through a different lens because of their legal status, tenant protections, and operational realities.

1. Rent Stabilization and Income Limits

If your property contains more than six legal SRO units, it is likely covered by New York’s rent stabilization laws. This means:

- Annual rent increases are capped by the NYC Rent Guidelines Board, regardless of market demand.

- Tenants have strong renewal rights and can’t be evicted without legal cause.

- Even after a tenant moves out, the unit often remains rent-stabilized for the next occupant.

From an investor’s standpoint, this creates a ceiling on potential rental income, limiting how quickly returns can grow compared to unregulated properties.

2. Niche Buyer Pool

Buyers for regulated SRO properties are a specialized group — typically investors who already operate rent-stabilized buildings. While they understand the rules, they also expect a price discount to offset:

- Long-term tenant protections

- Conversion and renovation hurdles

- The need for specialized property management to stay compliant with city regulations

A smaller buyer pool often translates into slower sales and more aggressive price negotiations.

3. Appraisal Methods That Depress Value

Vacant Class A townhouses are usually appraised based on comparable sales in the neighborhood. In contrast, an SRO townhouse with rent-stabilized tenants is often valued using the income capitalization method, meaning:

- The property’s value is tied to its current net operating income, not its potential post-renovation value.

- If current rents are significantly below market, that reduced income is reflected in the appraisal, even in prime locations.

4. Maintenance and Compliance Costs

Most SRO townhouses are pre-war buildings, which means they have older systems, higher repair costs, and require more frequent inspections. Maintaining compliance with NYC’s housing and safety codes — from fire egress to boiler maintenance — can eat into profits and deter casual buyers.

Bottom Line

The combination of regulatory constraints, reduced income potential, and a specialized buyer pool means that SRO townhouses with rent-stabilized tenants typically sell for less than equivalent Class A properties in the same neighborhood.

That said, strategic owners can still unlock value, whether through legal conversion, targeted sales to specialist investors, or long-term hold strategies that align with city rules.

Common Situations for Owners and Heirs of Class B Units and SRO Townhouses

In my private advisory practice with townhouse owners and their heirs, I’ve observed how Class B units and SRO townhouses can serve as both sources of income and sources of stress. Although each property has its own unique story, certain patterns tend to repeat. The specifics may differ — the neighborhood, the building’s age, the number of tenants — but the challenges are remarkably similar. Below are real-life examples (with details changed for privacy) that demonstrate how these situations develop and highlight the pivotal moments when owners and heirs must choose their next steps.

1. The Longtime Owner Who Rented Rooms to Survive Rising Costs

In the early 1980s, a family purchased a townhouse on Edgecombe Avenue in Central Harlem through a city program that sold off properties it had seized for unpaid taxes. For years, it was a bustling two-income household. But after the husband’s passing, the widow found herself living alone in the large home, with grown children living in other boroughs.

To help cover rising bills, she began renting out spare rooms — informally, without leases, just cash payments. At the time, it seemed like a practical, temporary solution. Decades later, with her health declining, she planned to move closer to her children for support. That’s when she discovered the unintended consequence of those early arrangements: the building’s Class B status meant her tenants had strong legal protections, and they refused to leave amid New York City’s ongoing housing crisis.

The result was a hard truth — her property was now classified with rent-stabilized SRO units, making it worth significantly less than an equivalent Class A townhouse in the same neighborhood.

2. The Older Owner Facing Maintenance Overload

I once handled the quiet, off-market sale of a townhouse that had been in the same family for generations. The elderly owner had inherited it from her parents and initially managed the upkeep without much trouble. But over the years, the demands of the property — constant repairs, code compliance, and the complexities of rent regulations — became overwhelming.

To help offset expenses, she began renting portions of the townhouse. Unfortunately, because the building had SRO status, the rental income was tightly capped by stabilization rules. The revenue simply couldn’t keep pace with rising property taxes, utilities, and maintenance costs.

Eventually, she turned to a reverse mortgage to cover the shortfall. While this allowed her to stay in her home, it also meant drawing heavily on her equity, which significantly reduced the value of her estate. By the time the property was sold, much of its potential value had already been absorbed.

3. The Heir Who Becomes a Landlord Overnight

I know of a man who unexpectedly inherited a townhouse in South Harlem under unusual circumstances. The property had belonged to his uncle, who willed it to the man’s mother. However, because his mother passed away before his uncle, ownership passed directly to him.

The uncle, who never married or had children, had lived in the townhouse for decades. In his later years, the upkeep became too much, especially as his health declined. To help cover expenses, he rented out two rooms. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, those tenants stopped paying rent, a blow that the uncle endured without pursuing eviction.

After the uncle’s passing, the new owner stepped in with little knowledge of rent stabilization laws. Seeing only two tenants he believed had taken advantage of his ailing uncle, he moved to terminate their tenancy. The response was swift: the tenants sued, claiming rights under stabilization laws, and are now demanding a payout equal to 82% of the property’s current value.

This situation underscores how quickly an uninformed decision — even one made in frustration-can escalate into a costly legal battle when Class B or SRO regulations are involved.

4. The Family Facing a Crossroads

Some families face a joint decision: keep the SRO townhouse as an income property, convert it to a Class A property, sell it outright, or utilize tools like a reverse mortgage to tap into equity without selling the property.

In these cases, the challenge isn’t just financial — it’s emotional. A property may hold decades of family history, yet its current legal and economic realities demand a businesslike approach. Families who make decisions early, with a clear understanding of city regulations, tend to achieve the best outcomes.

Your Options If You Own a Class B Unit or SRO Townhouse in NYC

Once you understand your building’s legal classification, tenant rights, and market realities, you can start mapping out your next move. The right path depends on your goals, finances, and how much time you — or your heirs — want to stay involved.

1. Convert Class B Units to Class A

If your property is vacant or has only a few tenants, one of the most value-boosting strategies is to convert SRO units into Class A apartments or restore the building to single-family use.

- Why it works: Class A units are for permanent residence and aren’t subject to the same rent stabilization rules as SRO units. This can significantly increase your market value and expand your pool of potential buyers.

- What it takes: Filing plans with the NYC Department of Buildings, hiring an architect familiar with SRO-to-Class-A conversions, and meeting today’s building code standards.

- The challenge: If tenants remain, relocation can be a legally sensitive and expensive process. Approvals also take time, so this is not a quick fix.

2. Sell With Tenants in Place

If conversion isn’t realistic — or if you need liquidity quickly — selling with tenants in place is often the most direct route.

- Who buys: Investors who specialize in regulated properties and already operate SRO buildings.

- The trade-off: Expect a price that reflects regulated rental income, not market-rate potential.

- The advantage: You avoid legal relocation battles and can close faster than a conversion timeline would allow.

3. Explore a Reverse Mortgage (For Senior Owners)

If you’re 62 or older, own your property outright (or have a small mortgage), and want to stay in your home, a reverse mortgage can provide a steady cash flow.

- Use cases: Covering repairs, paying property taxes, or supplementing retirement income.

- Caution: This reduces equity for heirs and isn’t ideal if selling in the near term is part of the plan.

4. Plan an Orderly Transition to Heirs

If you intend to pass the property down, don’t wait for your heirs to inherit a legal and operational puzzle.

- Organize legal documents and certificates of occupancy

- Maintain an updated tenant roster with lease copies

- Discuss a realistic plan for management or sale

Proactive planning prevents rushed, emotionally charged decisions that can hurt the property’s value.

Checklist: Preparing Your Class B or SRO Townhouse for Sale or Transition

Whether you plan to sell, convert, or pass your townhouse to heirs, getting your house in order (literally and legally) will save time, reduce stress, and help you protect value.

1. Confirm the Building’s Legal Status

- Pull your certificate of occupancy from the NYC Department of Buildings (DOB) to see if the property is officially Class B (SRO) or Class A.

- Check HPD (Housing Preservation and Development) records for the registered number of units.

- Have a housing attorney or architect interpret the findings — small details here can change your strategy entirely.

2. Audit Your Tenant Situation

- Create a current tenant roster with lease copies or proof of month-to-month arrangements.

- Document rent payment histories.

- Keep a log of any repair requests, DOB violations, or HPD complaints — buyers and attorneys will want to see this.

3. Gather Financial Records

- Property tax bills (and proof of payment) for at least the past two years.

- Utility costs if you pay for any tenant services (heat, water, gas, electricity).

- Receipts for repairs, renovations, or upgrades — even small ones, as they show ongoing maintenance.

4. Assess the Building’s Physical Condition

- Hire an independent inspector to flag structural issues (foundation, roof, façade) and systems health (boiler, plumbing, electrical).

- Address life-safety items first (fire escapes, egress, smoke/CO detectors) — violations in this area can delay sales or conversions.

5. Assemble Your Professional Team Early

- A real estate attorney who knows NYC rent stabilization and SRO law.

- A broker with proven experience selling regulated multi-unit properties.

- An architect, if conversion is on the table — preferably one who has completed Class B to Class A transitions.

Pro Tip: Don’t wait until you’ve decided to sell or convert to do these steps. The earlier you prepare, the more leverage you have when it’s time to negotiate.

Why Timing Can Make or Break Your Outcome

In NYC real estate — and especially with Class B units and SRO townhouses — time is not a neutral factor. The longer you wait to act, the more you risk eroding both your options and your property’s value.

1. Repairs Only Get More Expensive

Older townhouses with multiple units often have aging roofs, boilers, plumbing, and electrical systems. A roof leak ignored for a year can turn into a six-figure repair once water damage spreads. Deferred maintenance is one of the fastest ways to lose leverage with buyers or drive down an appraisal.

2. Tenant Rights Strengthen Over Time

With rent-stabilized SRO tenants, longevity works in the tenant’s favor, not the owner’s. Long-term tenants usually pay rents well below market rates, and the longer they stay, the greater the gap between the regulated rent and market value. That rent gap is directly reflected in your property’s income-based valuation.

3. Market Conditions Shift — Sometimes Overnight

NYC real estate runs in cycles. High interest rates, changes to rent regulations, and investor sentiment toward regulated buildings can swing within months. Selling during a strong investor cycle can mean tens of thousands more in your pocket; missing that window can have the opposite effect.

4. Estate and Tax Planning Benefits Fade

If you plan to pass the property to your heirs, early planning can help reduce estate tax exposure and facilitate a smoother transition. Waiting often means your heirs inherit a legal and operational puzzle at the worst possible time — after your passing, when stress and time pressure are highest.

Bottom Line:

Delaying decisions doesn’t “keep your options open” — it quietly narrows them. Acting while you have control over the property’s condition, occupancy, and timing gives you the best shot at maximizing value.

Conclusion: From Historic Housing to Strategic Decisions

Owning a New York City townhouse with Class B units or SRO rooms isn’t just about bricks and mortar — it’s about inheriting a century of housing policy, economic shifts, and legal protections that have shaped both the city and the building you now control.

From their origins as elegant single-family homes, to their adaptation during the Great Depression, to the preservation laws that locked in rent stabilization, these properties have always been about balancing affordability with owner reality.

Today, striking that balance is more complex than ever. Regulations meant to protect tenants can also limit your choices and lower your property’s market value. But with the proper knowledge, preparation, and timing, you can turn a complex situation into a clear path forward — whether that means conversion, a strategic sale, a reverse mortgage, or a well-planned transfer to heirs.

The key is not to wait. The sooner you understand your building’s legal classification, your tenants’ rights, and your market position, the more options you’ll have and the better your financial outcome will be.

Important: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Every building — and every family’s circumstances — is unique. Before taking action, speak with a qualified NYC real estate attorney and housing law expert.