Key Takeaways:

- Massive, Built-In Revenue for NYC: Billionaires’ Row towers have paid over $213M in transfer taxes and will contribute $110M+ in property taxes in FY2025 — all automatically assessed and enforced by the city.

- Outdated Tax Law Creates Misperceptions: Luxury condos are taxed like rental buildings under a 1980s law meant to protect middle-class homeowners — not designed with billionaires in mind.

- More Than Homes — They Fuel the Local Economy: With hotels, retailers, and full-time staff, these buildings generate layers of sales, business, and payroll taxes that ripple far beyond their walls.

Receive the Private Edition

A version of this article appeared in the Private Edition newsletter. Sign up to receive future editions straight to your inbox.

Billionaires’ Row

In the debate over property taxes in New York City, few topics stir as much reaction as Billionaires’ Row.

The luxury towers lining 57th Street have become visual shorthand for excess. However, behind the symbolism lies a less-discussed truth: these buildings generate significant, sustained revenue for the city.

They pay transfer taxes every time a unit is sold or transferred. They pay property taxes every year. And the hotels, retailers, auction houses, and full-time employees that operate within them generate additional layers of economic activity — and tax revenue — that ripple far beyond the buildings themselves.

Some contributions are obvious. Others are invisible to the casual observer. But they all add up. These buildings are not freeloaders. They are, in fact, dependable contributors to the city’s budget.

This isn’t to say the system is flawless or that it doesn’t deserve reform. However, the public narrative — often shaped more by emotion than data — rarely reflects the full picture. When you follow the numbers, a different story emerges.

New York City Gets Paid First At Market Price

Before a resident moves in, before the lights go on, before a piece of furniture is delivered — the City of New York has already been paid.

That payment comes through the Real Property Transfer Tax (RPTT). For residential transactions exceeding $500,000, the city collects 1.425% of the sale price, paid at closing, based on the actual market value.

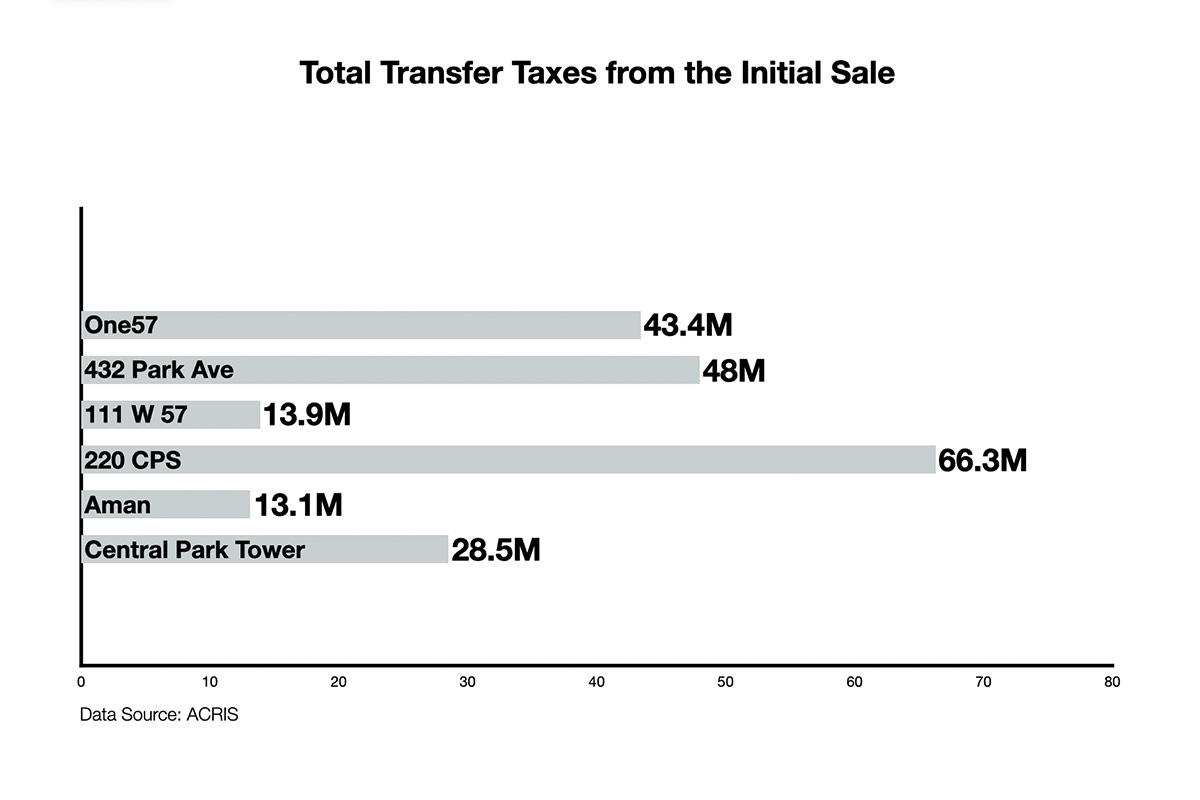

Since the first sale at One57 in 2013, these six towers have paid over $213 million in transfer taxes to the City of New York.

These are not negotiated payments or deductions. They are automatic — hardwired into the transaction itself.

The Recurring Contribution

Every year, these towers contribute to the city’s general fund through property taxes. Owners don’t file returns. They don’t apply for deductions. The city assesses the building, issues a bill, and the bill gets paid.

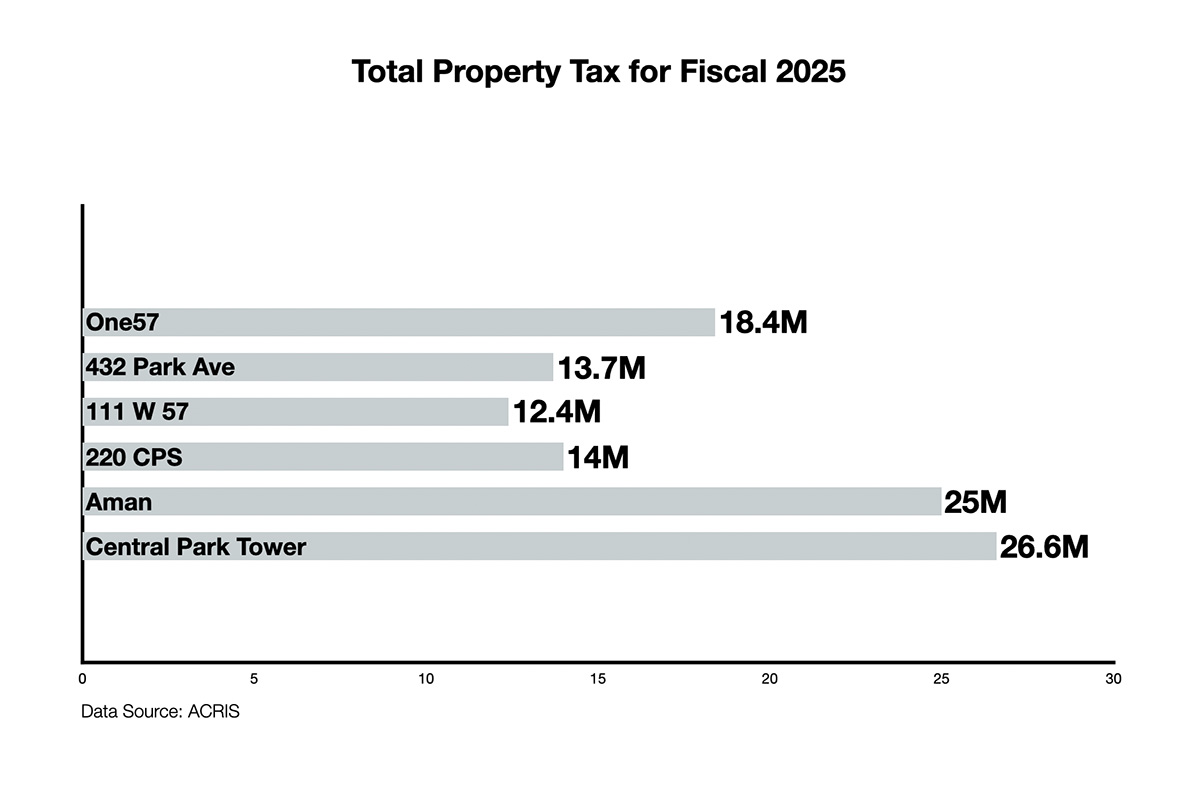

For Fiscal Year 2025, the six buildings listed above will pay over $110 million in property taxes.

Critics point to how low these bills appear compared to sale prices — and that criticism is fair.

Some condos here sell for tens of millions, even hundreds of millions of dollars. Yet under New York’s Class 2 tax formula, these buildings are assessed based not on sale prices, but on comparable rental income. And since there are few, if any, rental buildings that resemble a $75 million condo tower, the result is an artificially low valuation — and a lower effective tax rate.

This assessment structure produces disparities. Compared to a middle-class home in Queens or Brooklyn, the tax burden can seem inverted.

But that nuance is often omitted. Instead, headlines suggest the wealthy aren’t paying anything at all. It’s a distortion. And it leaves the public with a skewed sense of what’s actually happening.

Yes, the federal tax code is full of loopholes. But this is different. New York City’s property tax is fixed, automatic, and enforced. If you own a unit, you are responsible for the payment.

More Than Homes: Multi-Use Revenue Engines

These towers are more than residences. Many also house hotels, restaurants, retail spaces, wellness centers, and offices — all of which contribute in layered ways:

- Sales tax on goods and services

- Business income tax at both the city and state levels

- Payroll tax from hundreds of full-time jobs

Staffing alone — including concierges, doormen, engineers, and hotel personnel — creates long-term employment, much of which is unionized. The wages are taxed. The businesses are taxed. The spending that flows through and around these buildings sustains a quiet ecosystem of local economic activity.

While the focus often centers on assessed values, the broader contribution is persistent and multidimensional.

A Law Written in Crisis

To understand how these buildings are taxed, you have to understand the origin of the law.

In the 1970s, New York City was in a state of crisis. Buildings were abandoned. Residents were fleeing. Tax revenue was collapsing. In response, the state passed S7000A, a sweeping reform aimed at stabilizing the property tax base and preventing further population loss.

The law created four property classes. Class 2, which includes all multi-unit buildings — from modest co-ops in Queens to luxury towers on Central Park — was assessed based on comparable rental income, rather than volatile market prices.

According to the Independent Budget Office, this law wasn’t written with billionaires in mind. It was designed to avoid overtaxing working- and middle-class homeowners during a fiscal freefall.

Fast-forward to today, and the law remains largely unchanged. The world around it, however, has shifted. A luxury market has emerged. Sales prices have soared. However, the valuation model remains tied to rentals that no longer provide meaningful comparisons.

That’s the source of today’s frustration. However, claiming the system was built to protect the rich overlooks its actual history. And pretending these towers don’t pay taxes ignores the facts.

Conclusion: Not Defended, Just Counted

This is not a defense of luxury condos. It clarifies their role in the city’s fiscal system.

Billionaires’ Row may be provocative. But its tax contribution is real, measurable, and built into the structure of how New York City collects revenue.

These buildings pay. Automatically. Substantially. And dependably.

They don’t just define the skyline — they help sustain the city beneath it.